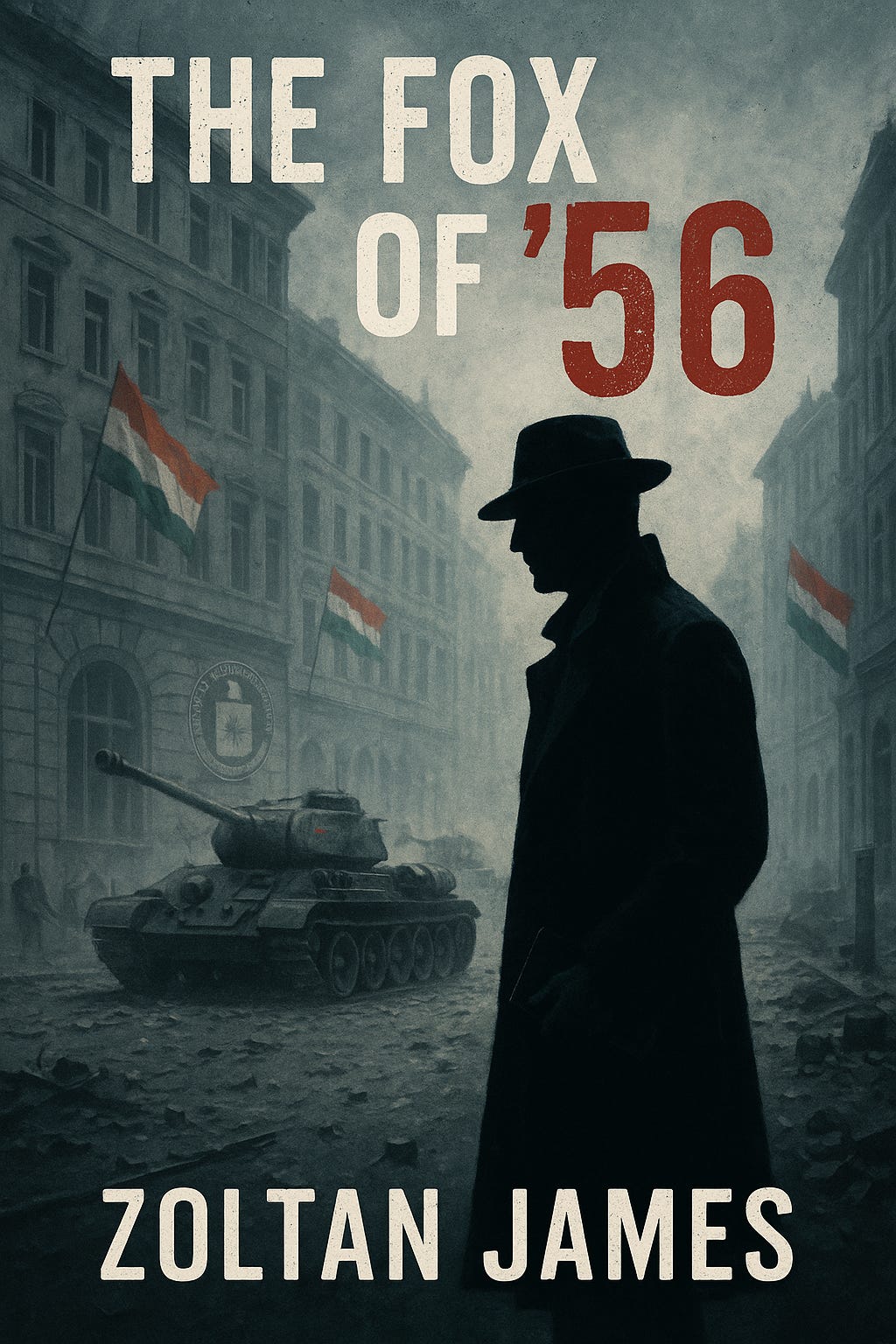

In 1956 as Hungarians mount their revolution against the Soviets, CIA agent Henry Caldwell is sent to Budapest to monitor activities. But when he sees Katalin, the love of his love who disappeared four years ago, he’s confused. Through the war-torn streets, Henry finds himself in a deadly game of cat-and-mouse where trust is scarce and survival uncertain.

Chapter 8

First thing in the morning, I returned to the Café Hungaria for breakfast and to touch base with my handler, Steve. I hoped he had intel about why Orlov would be meeting with Kat at midnight.

I changed my normal walking route to avoid the fighting and passed by the Museum of Applied Arts when I realized I’d made a mistake. T-34 Russian tanks rolled down the street with menace. They stopped at the intersection, the engine’s rumble echoed off buildings, and without notice fired at a building across the boulevard. Bricks and glass exploded into the intersection. People ran and screamed. More chaos on a bright autumn day.

A group of young Hungarians hunkered down behind a barricade hurling bricks at the tank in hopes of jamming up the tracks and wheels. Around the corner, white-capped paramedics transported wounded to the hospital.

I interviewed one of the Freedom Fighters and learned that when the tank became incapacitated, the Soviet personnel opened hatches and waved white flags to surrender. The Hungarians dismantled the machine gun from the tank and would use it again against the Soviets. I filed this story to Reuters later in the day. The story carried a hopeful ring to it and I knew the editors would welcome this slice of life from the streets of Budapest.

Despite the ongoing street battles, the restaurant was filling up quickly. The cafe was one of a few Budapest coffee houses where politicians, journalists, poets, professors, and business men gathered to share news of the day. If one listened closely, one could get a sense of dread and hope that floated over the city.

I grabbed a table in the corner and before I could catch Steve’s eye to join me an irascible man, in a ragged coat, shuffled past me. He parked in the middle of the aisle grumbling and making snide remarks to the old, white-coated waiters, who giggled at him behind their egg-stained sleeves. The man politely laid pamphlets at every table. I assumed him to be another poet trolling for free coffee. When he’d disposed of all his printed pieces, the man stood in the aisle, head held high, silent as a statue, until all eyes turned his way. When he had their attention, he pointed a defiant finger in the air and said,

“We are all attending a funeral. We must not, we shall not forget. And we will name the murderers.”

He bowed to polite applause. One table of gentlemen invited him to join them for coffee. The poet seemed pleased and eagerly joined his new friends.

I finally caught Steve’s eye. He brought a pot of coffee and sat heavily across from me.

“You look tired, Steve.”

“Maybe we trade places. You run restaurant, you keep snarky old waiters happy, and wash dishes when the dishwasher doesn’t show. I’ll go out at night and walk in shadows and act suspicious.”

“Steve. Little edgy this morning.”

“My dishwasher was shot last night in front of the cinema. He was unarmed.”

“Oh, my God. Sorry.”

“Me, too. His name was Laci. He worked hard. Wanted to become chef someday. And I apologize. This fighting and killing worries me.” He poured coffee. “Tell me what you know, I do same.”

I told him about Kat’s meeting with Orlov in the shadows by the World War I monument and the bits of conversation I overhead about scientists.

“Why don’t you ask your friend Katalin? Go to the source.”

“She’s not talking to me.”

“Ah, sadly in love, there is more bitterness than sweetness.”

“What does that mean?”

“Old Hungarian proverb. You want a relationship? You have to work at it, my good friend.”

“I’ll think about that. But right now, I need your help. What scientists could they be plotting against or about?

“Scientists, eh? We have many scientists in Hungary.”

“What would Orlov’s interest be?”

“Hard to say. Could be nuclear, could be mathematics, maybe formula for better pancakes.”

“What?”

“Russia has terrible pancakes.”

“Maybe we should focus on nuclear.”

“You’re right,” Steve said, “Say, how about we order some palacsinta. You hungry?”

The thought made my mouth water. Hungarian pancakes were one of my favorite menu items. They are thin crepes, rolled, and sprinkled with powdered sugar and filled usually with either apricot, strawberry, or blueberry jam. I ordered the apricot. The gray-haired waiter, Kalman, shuffled to our table and took our order with seeming displeasure.

“Steve, why do you keep old Kalman on here. He never smiles and acts like taking an order is an imposition. I think he hates his job.”

“I know. I know. I have to watch him constantly.” He leaned in and whispered. “I think he’s a communist.”

“If you can’t trust him, fire him.”

Steve lowered his eyes. “Kalman, is my wife’s cousin.” Steve began again, “You know, my friend, you and I are alone here.”

I glanced around. His café was full. “What do you mean?”

“Not the café. You’ve heard about the crisis at the Suez Canal, yes?’

“Of course, my editors at Reuters are constantly bickering over which story, Hungary, or Suez, deserves more attention. In London, at six in the morning, they lead with Suez. By ten o’clock, Hungary is the big story.”

“Ah, now, maybe you understand why our father across the pond (he always liked to refer to the CIA as his father, for some odd reason) has more agents in Egypt than in Hungary. Why Eisenhower is giving only lip service to Hungary. And we are mere pawns in this chess game.”

I admitted to Steve, these were things I hadn’t given much thought to. I reminded him that when I was seeing outmanned, outgunned Hungarians fighting against bestial tanks, one doesn’t think about the Suez Canal.

“Understandable. But the Soviets know this, of course that Eisenhower is no longer interested in fighting wars, and so they are taking advantage. They know they can roll through our tiny country without restraint. Look at the UN. They simply condemned the Soviet action here verbally, but because the British and French have acted in Suez, and the Russians are saber rattling, the UN sent UN forces there. Tell me. Why not here? Meanwhile, the Soviets are emboldened to overthrow our tiny rebellion. And, they make nuclear threats over Suez. See the chess game here?”

“And Orlov must think some Hungarian scientists have a new theory or application to improve nuclear arms? Is that it?”

“Ah, not scientists, plural, my friend, but singular. He wants one and only one.”

“Steve. Stop being coy with me. Who is it?”

“All I’ve heard from my sources is there is only one scientist they are interested in.”

“And?”

“That’s what you need to find out.”

Author’s Note: The comment by the poet in the aisle of the Cafe Hungaria is one I appropriated from Hungarian poet Gaspar Nagy (1949-2007) and it’s the final stanza from his 1983 poem, “An Everlasting Summer. I Am Older than 9.” The real stanza reads as:

Once there will be a funeral

We must not forget

And have to name the murderers.

His poem was about the unmarked grave of Imre Nagy (1896-1958), the executed prime minister in the 1956 revolution, and about his unnamed murderers. In the Hungarian version of the poem he hid Imre Nagy’s initials “NI” which appear as the last two letters of each line. (In Hungary, the given name traditionally comes after the family name). The hidden meaning escaped the eagle eyes of the censors and the poem was published. Later, when the communist authorities realized the subterfuge in the poem, they stripped Gaspar Nagy of his post as Secretary to the Hungarian Writers Union.

Imre Nagy was a communist politician and served in several government roles in the communist regime. When the students first marched on Radio Budapest in October 1956, one of their sixteen demands was the reinstatement of Nagy as prime minster. He led the Hungarians in the revolution against the Soviets. He only served in the role of prime minister for eleven days. Because of that he was sentenced to death and executed for treason in 1958. The Soviets ignominiously buried him in an unmarked grave. In 1989, after the Iron Curtain fell, Nagy was reburied with full honors.

I'm ĺearning so much! I look forward to the author's comments. This is definitely your strongest work and has rising to the level of....I don't want it to end.

This story started so strong, and keeps gaining strength. When I was little, we would drive by the Hungarian Freedom Park in Denver. My grandfather would tell me stories about what the Hungarian people endured. I was too young to understand, but as time went on I realized the importance of our freedoms in this country. Thank you for shedding light through this incredible work.