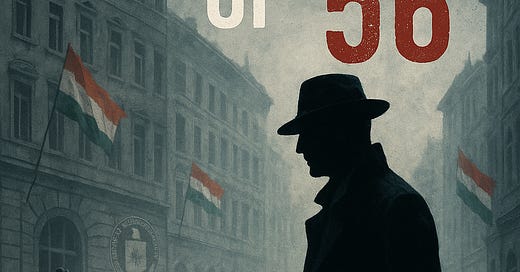

In 1956 as Hungarians mount their revolution against the Soviets, CIA agent Henry Caldwell is sent to Budapest to monitor activities. But when he sees Katalin, the love of his love who disappeared four years ago, he’s confused. Through the war-torn streets, Henry finds himself in a deadly game of cat-and-mouse where trust is scarce and survival uncertain.

Chapter 15

Steve shook his head. “No. No gun. No gun. You will only get killed. I will not have it.”

Steve was frustrating me. He was my local case manager, and I considered him a friend. Maria, too. But I needed help and I needed it now. “Steve. We can’t sit here while Orlov pirates Dr. Vadas off to Russia. You admitted that you understand the stakes.”

“Yes. Of course, my friend, but I won’t allow it. I don’t want you killed over something we cannot control. Father said to stand down. I think he means ‘sit down’ but this is order. Not me talking.”

I didn’t have my copy of The Prince with me but I remembered some key lessons. The one standing out for then was “adaptability is crucial. Successful leaders are flexible and easily adapt to changing circumstances, sometimes they act with mercy, and other times with cruelty.” Right now, I needed a bit of both.

“All right, Steve. I understand. I don’t like it, but I understand.”

“Good. Good,” he said. He stood and pointed at me like a doting father—not our ‘father’ his nickname for the CIA as he calls them, but like a real father. “Just breathe deep, relax. Sit still and let your head heal. I go close up restaurant. Then we talk some more. Okay?”

“Fine. Okay.” I waited for him to leave. I shook off the scarf and ice pack from my head and bolted for the back door.

# # #

If Steve wasn’t going to help me get a gun, I knew where I could find one. My other friend, Zsolt, the young revolutionary. I picked my way across the broad boulevards of Budapest taking wide arcs around the center to avoid the fighting.

The afternoon sun slowly faded behind the Budapest hills while the fog of smoke and dust created by shooting, by fires set by Freedom Fighters, and the rubble of destroyed buildings hung in the air.

When I reached Zsolt in his makeshift office on the second floor of the Corvin Cinema, he greeted me with a broad grin. “Do you hear that?”

“No. What?” He motioned me to join him and a half-dozen Freedom Fighters at the window.

In the distance, Soviet tanks were retreating from the city’s center. Young Hungarians danced on tops of dead tanks. What I heard was eerie. No shots were being fired. Here and there laughter echoed through the streets, as if a new sense of euphoria had rolled through the city the way fog rolls down from the hills.

“What is happening?” I said.

“Premier Nagy has announced an armistice for Hungarian troops to stop fighting and the Soviets have agreed to stop as well. We have won our independence. No thanks to our Parliament which argued and scratched their heads. It was the people, in the streets, who made our revolution.”

Zsolt and his friends broke out bottles of wine.

I was flabbergasted. For the tide had turned in this battle. The little country of Hungary had seemingly defeated the the giant Russian bear. The ragtag group of Hungarian fighters, who literally had nothing, had armed themselves with weapons seized from the Soviets and used street-smart ingenuity. I once heard Zsolt say to his followers, “If you don’t have a gun, the Soviets will bring one to you.”

Guerrilla warfare tactics, barricades made from overturned cars and wagons, and Molotov cocktails ruled the day. While the Russian tanks destroyed houses and buildings, they never controlled any of them.

Zsolt pointed to a Polish newspaper, “Look at this. The reporter laments his country had done nothing to help us. He writes of his anger toward neighboring Czechoslovakia, which actually sided with the dog Russians.” He quoted the author: “Sadly we must admit that the Hungarians acted like Poles. The Poles acted like Czechs. And the Czechs acted like swine.” Zsolt added, “But the Americans didn’t act at all.”

That hurt and he was right. All we did was offer bromides and encouragement via Radio Free Europe, while the American Eagle focused her beady eyes on the Suez Canal. I felt ashamed.

But I was also glad for Zsolt and all the Hungarians who had driven out the Russians. They had done so at great cost. Children, women, men of all ages had died in their fight to secure freedom from Russia. Nevertheless, I had a spy to catch. I took Zsolt aside from his partying friends. “Zsolt. I need a gun.”

He raised an eyebrow. “A journalist with a gun. That is double trouble.”

I pulled him out of the room and into the hallway where I could speak freely. I admitted to him who I really was. He was shocked but not really surprised. He said, “I always suspected any American here, at this hour, must be a spy.”

“I’m not really a spy. I’m more of an observer. But I need to stop Orlov and save Dr. Vadas. Can you get me a gun?”

He eyed me with great curiosity and without speaking reached behind his back and produced a pistol. “Here. Eight shots. Should be plenty.”

I held the gun flat in my palm. He explained it was a Tokarev, a Hungarian pistol with the socialist symbol of Hungary ground into the grip. “I took it off a dead secret security policeman.”

“Did you kill him?”

He shrugged. “It doesn’t matter. Use it carefully, my friend.”

I have a question. I'll message you.